Wheat Self-Sufficiency Requires Sustainably Closing the Yield Gap in CWANA

Scientific Blog By Dr. Krishna Devkota , Dr. Mina Wasti-Devkota , and Dr. Vinay Nangia.

Found in flatbreads, loaves, bulgur, freekeh, and couscous, wheat is a regional staple woven into the culture, nutrition, and economic stability of millions across Central and West Asia, and North Africa (CWANA). Yet, the combination of growing populations, climate change, and water scarcity has left many countries importing over 40% of their wheat supply, with some as much as 100%.

Our research at ICARDA, under the Scaling for Impact (S4I) and Sustainable Farming Program (SFP), focuses on bridging the widening yield gap, the difference between what farmers currently produce and what is attainable under optimal rainfed or irrigated conditions using good agronomic practices (GAP). These practices, such as timely planting, recommended seed and nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) fertilizer rates, resilient crop varieties, and conservation agriculture, offer a science-backed route to food self-sufficiency and resilience in the region.

The Wheat Reality in CWANA

Across the region’s 24 wheat-producing countries, more than 49.6 million hectares are dedicated to wheat cultivation. However, average productivity stands at just 2.35 tons per hectare (t/ha) – approximately 37% lower than the global average. In 2023 alone, these countries spent a total of USD 21.1 billion on wheat imports, with Turkey, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Afghanistan leading the list.

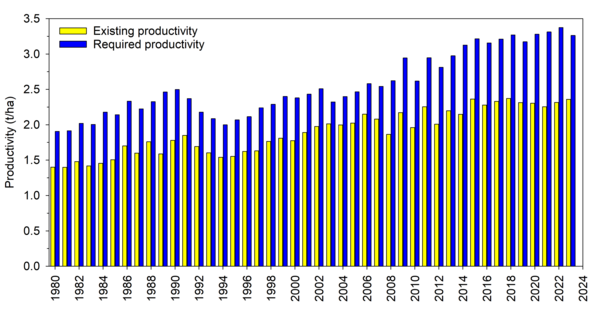

While yields have increased slowly from around 1.5 t/ha in the early 1980s to approximately 2.30 t/ha by 2023, the current yields remain significantly below the levels required for self-sufficiency, which is roughly 3.30 t/ha, leaving a persistent and widening self-sufficiency gap of around 1.0 t/ha. This gap varies across the region, from under 2.5 t/ha in Morocco and Uzbekistan, where self-sufficiency is within reach, to over 3–10 t/ha in Algeria, Egypt, and the Gulf countries, where it remains a distant goal.

The Water-Yield Equation

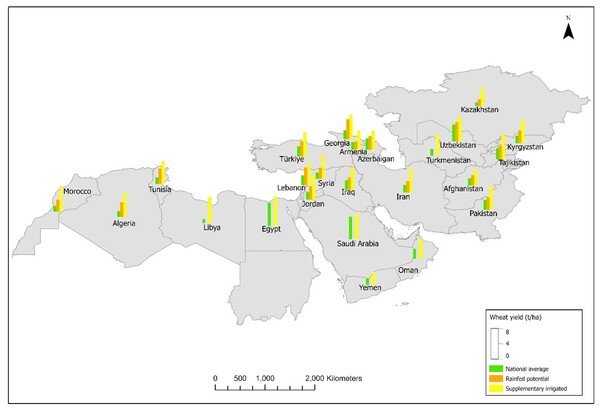

Water defines the success or struggle of every wheat season across CWANA. ICARDA’s long-term Agricultural Production Systems sIMulator (APSIM) simulation study across 24 wheat-producing countries shows that under rainfed farming, in good rainfall years (over 250 well-distributed millimeters), combined with GAP, yields could reach 3.86 t/ha, ranging from 2.0 t/ha in Kazakhstan to 5.8 t/ha in Tunisia and Morocco, attaining an average yield gain of around 1.51 t/ha, or 38.6%. Under irrigated conditions, with supplemental deficit irrigation at 50% of available water content and integrated GAPs, the average yield could soar up to 6.5 t/ha, ranging from 3.72 t/ha in Yemen to 8.5 t/ha in Egypt, demonstrating an average attainable yield gain of around 3.84 t/ha or 59%.

Ultimately, water availability shapes what’s possible on the ground, but not all countries face the same hydrological reality. In the driest parts of CWANA, farmers rely almost entirely on irrigation. For example, in Libya, wheat farming relies on 554 mm of irrigation water to just 2.6 mm of rainfall., Egypt (518:46), Saudi Arabia (513:90), Oman (320:64), Yemen (364:171), Turkmenistan (409:141), and Pakistan (356:194).

Rainfall is more generous across the Mediterranean and Caucasus belt where limited supplemental irrigation is needed: for example, in Lebanon (132 mm irrigation to 665 mm rain), Türkiye (117:469), Georgia (91:486), Algeria (176:411), Azerbaijan (84:406), and Tunisia (129:368).

Other countries, such as Morocco (222 mm irrigation to 296 mm rain), Jordan (238:370), Kazakhstan (284:265), and Syria (254:25), benefit most from moderate and timely supplemental (deficit) irrigation.

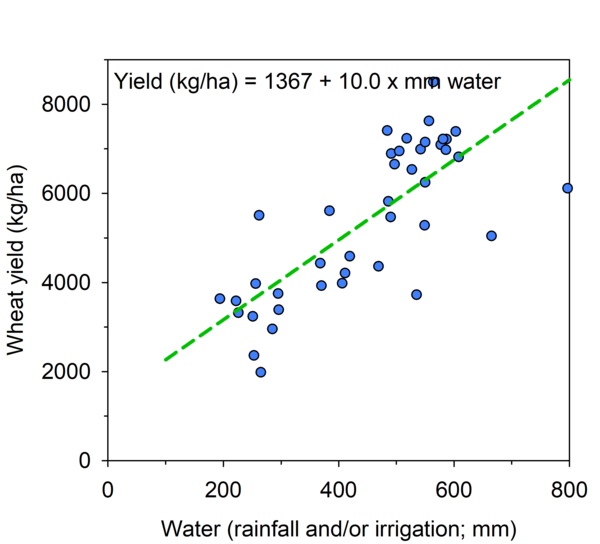

Our data (Fig. 3) shows that with every additional 100 mm of rainfall or irrigation water, wheat yields can increase by 1.0 t/ha, roughly equivalent to a 10 kg yield increment per mm of water. Across a range of 200–700 mm, wheat yields range from approximately 2 to 8 t/ha, underscoring the direct relationship between water availability and productivity gains.

Good Agronomic Practices (GAP): Country-Level Insights

ICARDA’s field studies reveal that one-size-fits-all solutions don’t work. Each country needs strategies tailored to its local conditions.

In Morocco, where 83% of wheat is grown under rainfed conditions, farmers continue to face unpredictable rainfall. A national survey of 2,296 fields across 21 provinces found that the average rainfed yield was 0.9 t/ha, with yield gaps of 41% and profit gaps of 75%. Irrigated fields perform better, 4.0 t/ha with 29% yield and 34% profit gaps but still lag behind attainable levels.

The Farmers field survey from field experiments, and long-term simulations point to the conservation agriculture package, including no-till, residue retention, timely sowing based on soil moisture, targeted fertilizer use, resilient varieties, and cereal-legume rotations, as key to closing these gaps. These practices increased yields by 15-30%, stabilized production, and improved profitability. In areas with supplemental irrigation, applying 28–166 mm of water during the dry season improved yields by 2–3 t/ha, especially when combined with early planting and locally adapted varieties.

In Uzbekistan, average farm yields hover around 4.55 t/ha – significantly short of the 6.2 t/ha required for self-sufficiency, resulting in a national yield gap of approximately 1.65 t/ha. ICARDA’s research reveals that adopting conservation agriculture practices boosts yields by 26%, while the adoption of stress-tolerant varieties adds another 22%. Sowing time also proved decisive; fields planted between 15 September and 15 October achieved optimal yields, whereas delays could result in losses of up to 57 kg/ha/day.

In Egypt, surveys of over 2000 irrigated fields across its major wheat-growing governorates revealed that the attainable yield gap is about 3-3.2 t/ha across multiple governorates. The top-performing farmers achieved around 7.5-8.4 t/ha, significantly exceeding the national average of 6.5 t/ha. While the specific yield drivers vary by location, the evidence consistently suggests that success hinges on integrated solutions that include bed planting, improved irrigation management, resilient crop varieties, high-quality seed, and tailored soil fertility management practices, encompassing both organic and inorganic nutrients.

A Blueprint for the Region

The experiences of Morocco, Uzbekistan, and Egypt reveal that closing the wheat yield gap is achievable but only through context-specific, science-based strategies. One-size-fits-all approaches inevitably fail in a region defined by climate diversity.

The way forward lies in institutionalizing smart agronomy through policies that deliver field-level, data-informed advisories and incentives that support adoption. When farmers have access to drought and soil-health services, improved inputs, and climate-ready crop varieties, attainable yields can become actual yields across CWANA.