Back to life – a Badia story

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, and the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land, and Ecosystems (WLE). The authors would like to thank the members of the Al-Majidyya Men Association for enabling, supporting, and securing research on their land.

-------------------------------------

Natural vegetation, pollinators, birds - a whole ecological system that was recently a barren wasteland has been brought back to life through ICARDA’s work in the Middle Badia of Jordan on adequate and sustainable land management approaches.

The hilly terrain of the Badia of Jordan, which spans 80% of the country's total surface area, was not always so barren and desiccated. Until the 1960s, the Badia – home to 400,000 Bedouins and 85 percent of the country's livestock – was a healthy ecosystem providing an abundance of nutritious and rainfed forage for animals, sustaining the Bedouins' livelihoods.

But a confluence of factors, some man-made, others climate-related, have driven a progressive, yet inevitable, ecological collapse. Worsening droughts, patchy rainfall, violent flash floods, unsustainable land management, and livestock rearing practices have all played a part in this gradual land degradation, exacerbated by ill-advised irrigation schemes and resettlement projects.

The general loss of vegetation has turned once healthy soil into a hard, impermeable crust. Runoff rates have intensified, causing sedimentation of downstream water reservoirs, further limiting farmers' access to clean irrigation water.

Jordan is not the only country grappling with the detrimental effects of drought and desertification on its fragile ecosystem.

Ibrahim Thiaw, the Executive Secretary of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), declared during the fifteenth session of the Conference of the Parties (COP15) in Abidjan last month that land restoration is one of the most comprehensive solutions to combat this global issue - as it addresses many of the underlying factors of degraded water cycles and soil fertility loss.

"We must build and rebuild our landscapes better, mimicking nature wherever possible and creating functional ecological systems," Thiaw argued.

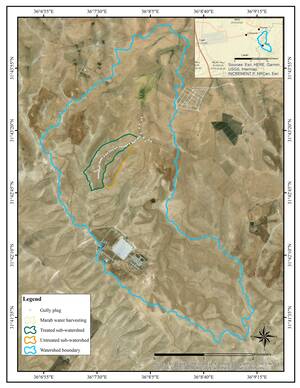

Since 2016, the ICARDA scientists involved in the Middle Badia rangeland rehabilitation project have followed that approach to bring an ailing ecosystem back to equilibrium using micro-water harvesting and out-planting native plant species. A Vallerani tractor-pulled plow dug intermittent half-meter-deep, semi-circular furrows in the soil on the contours of the experimental site.

Later, the scientists planted two seedlings of native Badia plants (either Atriplex halimus, Ratam, or Salsola) in each pit. The furrows have the capacity to store up to 200 liters of storm runoff, which can simultaneously dissipate the erosive energy of flowing water, support the plants’ growth, and percolate deep into the soil.

"For the first two seasons, grazing was forbidden so native shrubs could grow," explained Haddad. Botanical experts at Jordan's National Agricultural Research Center and older members of the local community - who were consulted to identify appropriate shrubs - settled on species tolerant to salt and drought that have historically thrived in the Badia.

Once mature, these plants constitute nutritious forage, stabilize the soil, make space for other species to grow, and limit excessive erosion and sedimentation accumulation.

In their paper recently published in International Soil and Water Conservation Research, lead author Mira Haddad and co-authors detail the results of ICARDA's rangeland intervention in Jordan. "It is extraordinary. In six years, the area's original vegetation cover has re-established itself, birds and insects have returned, and pollination has been reactivated," explains Haddad.

The study optimistically demonstrates that with sufficient time and adequate land management, even a deeply degraded ecosystem like the Badia can return to its former fertile state. To further validate the approach's effectiveness, scientists used the publicly available Rangeland Hydrological and Erosion Model (RHEM) and ran scenarios of water runoffs and erosion rate estimates.

Areas with meager vegetation cover were shown to produce far more runoffs, meaning more erosion potential than the newly restored area. "And not just by a little," explained Haddad. "We estimate that degraded rangeland areas lose three times more soil than the baseline and restored areas."

On the experimental site, which covers an entire sub-watershed of the Badia, the scientists placed a sensor camera in front of two low dams built across two wadis (gullies) to regulate the water flow. One of the dams, or "weirs," is in the treated area of ICARDA's restoration site, while the other is in the nearby - untreated (or 'control') area.

At precisely 6.34 am on February 28, 2018, the cameras captured the wadi water flow after a rainstorm in the two locations – which are less than a hundred meters apart. Video from the treated site (right) shows that water flow is low and contained. At the untreated site, muddy water is seen furiously cascading down the weir.

"If we could implement this approach in multiple other locations across the Badia, the overall reduction in soil erosion would be huge and significantly improve downstream conditions for dams and farmers," said Mira Haddad. Bedouin herders would have more forage for their animals, other plants would reappear, and the soil would be richer, and more stable.

"This once barren site is now teeming with life," Dr.Haddad concluded. "What we have been able to accomplish in just six years gives me hope for the region."